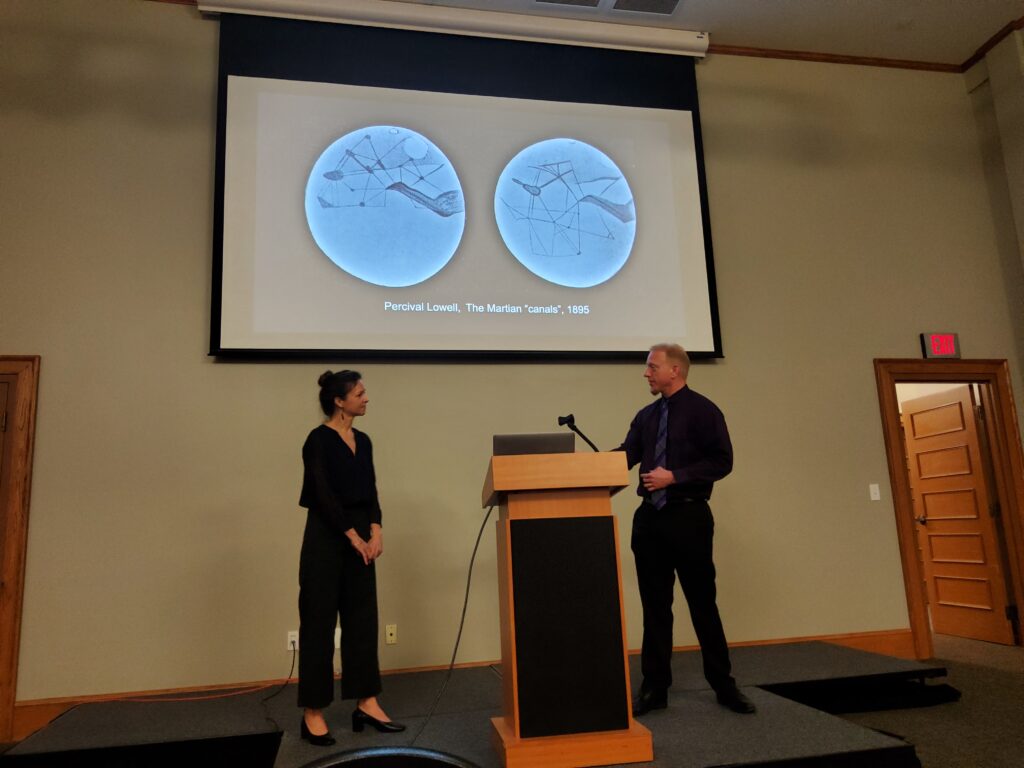

Subjects collide in an evening lecture that paint the similarities between art and science. On Mar. 29, UWG’s Astronomy professor Dr. Nick Sterling and Art Professor Casey McGuire gave a joint, interwoven lecture titled “Art Meets Astronomy: Communicating Scientific Discoveries” at the Newnan Carnegie Library for the “Other Night School” lecture series.

“We basically got paired because of our similarities in research, even though they’re separate disciplines,” says Casey McGuire.

During the Spring 2022 semester, UWG has hosted the lecture series “The Other Night School”. For one of the ideas, “The Other Night School” decided to pair very different subject teachers to formulate an interdisciplinary lecture.

“[Before Monday] we had only met on Zoom,” says Dr. Nick Sterling. “We’re on opposite sides of the campus. Yet, [the lecture] highlights the interconnections in ways that are not very obvious to the general public.”

Together they explored how their subjects intertwined and found that they had more in common than initially imagined. Over the centuries, astronomers and observers of the night sky have tried their best to recreate and capture what they saw through different forms of art.

“It even opened my eyes and helped me to look at it from a different angle about how we represent some of these images,” says Sterling. “Something that I take for granted as an astronomer. Like, these beautiful Hubble images are just false colors. Art and astronomy are deeply intertwined.”

A vast majority of space photography used in the science communities involve enhanced color, false color, miniature models or artist illustrations.

“The one thing for me about the history of astronomical photography is that we have been provided false color or artist interpretations of information since the mid 1800s,” says McGuire. “This is not a foreign concept when talking about false information or images. Truth in lies in imagery.”

Sir John Herschel was an English mathematician, astronomer, chemist, inventor and experimental photographer, or in fewer words, a polymath, meaning “having learned much” in Greek. Around the 1800s. Herschel is attributed as the artist that captured a highly detailed Calotype photo of a plaster model, and also falsely attributed to the Great Moon Hoax.

Also from the same time, James Nasmyth, polymath and artist, used plaster to create a moon model that he then photographed to capture a better image of what he saw through the telescope. Nasmyth is also attributed as depicting mountains on the moon, but he didn’t know at the time that there were none.

McGuire worked with Mark Schoon, another UWG professor, to join the observational astronomer artists and replicate space photography and concepts with practical effects. McGuire assures that the photos captured are not photoshopped or simulated but are created with what they had available in the art studio.

False color is another technique heavily utilized in many space photos circulating today. False color is the application of colors onto what would be invisible light to the human eye, the abundance of colors used and vibrancy is used to emphasize concepts beyond the visible light spectrum.

“You use false color to observe different properties,” says Dr. Sterling. “For example, one thing that’s really common in galactic astronomy is to overlay images. A physical light image over an x-ray image.

“Then you’re seeing two very different things, the very hot x-ray emitting gas that’s associated with a massive black hole that you don’t see just by looking at the stars,” continued Dr. Sterling. It’s used to create a sense of wonder, but also to better understand the results.”

The use of artist interpretations is a key element to theorizing complex mysteries such as the water maser, which is the emission of a galactic nucleus which is largely concealed behind clouds of space dust. Even today, with the advancement of telescopes and how to differentiate the spectrum of light, allows astronomers to find more and more details every day.

“Modern science is using false color to illustrate and communicate,” says McGuire. “First year art classes are all about still life: observation.”

You may also like

-

UWG’s Ingram Library Hosts Pop-Up Study Spot to Help Students Prepare for Finals Week

-

UWG Offers Mental Health Support And Academic Services To Maintain Student Success During Finals Week

-

UWG Alumnus Shares His Experience Exploring the Underground Flood Channels of Las Vegas

-

Georgia Students Simulate the Struggles of Dementia

-

UWG PR Students Score a Georgia Power Tour at Atlanta Corporate Office