Growing up as an African-American, there are always stories told about how hard people had to fight for equal rights. There was always emphasis on how much some suffered and lost. On the brighter side of the spectrum, there was also rejoice in learning most of those painful situations led to many breakthroughs and changed history. What makes it more real is when those stories hit really close to home.

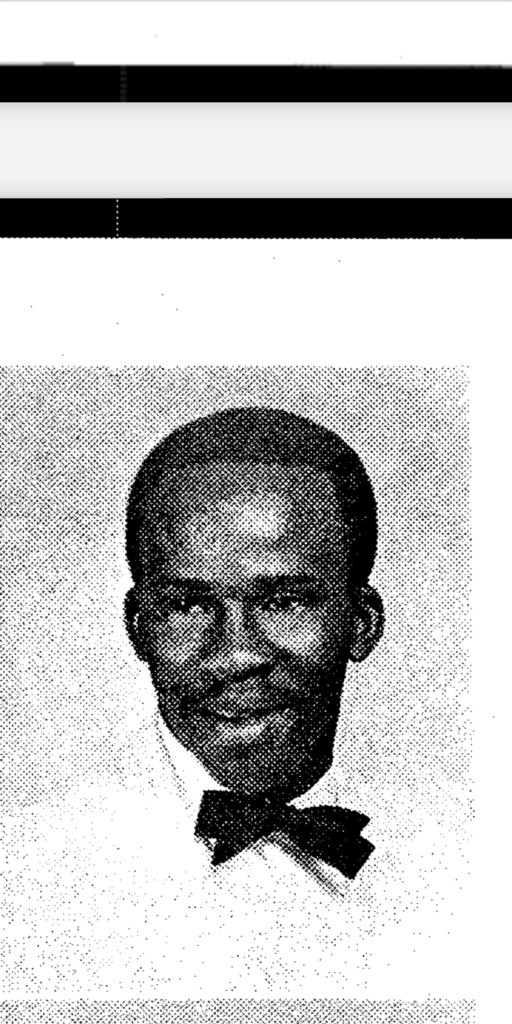

Although now he is known as Erskin Ulysses Harris, he was born and grew up as Ulysses Erskin Harris in Portsmouth, Virginia. Even though his name is not in books, he did make history. In September of 1966, on his first day of high school, Harris became one of just seven young African-American children selected for a mission: to be the first blacks admitted to one of Portsmouth’s all-white schools.

Before that fateful day Harris had no direct sense of segregation. It was when he reached third grade that he began to see less and less of his white counterparts. Spoke fondly of the days when he could play games openly with his white neighbors with no penalties.

“There used to be no tension between the races,” Harris mentioned more of his upbringing in the racist south. “But when we hit high school, some of us junior high, things just changed.”

It was not that much different throughout many places in the South. Although in 1954 when Brown vs Board of Education forbade segregation in schools, it never made anything equal for black students or their families. In the 50s and 60s, the act of keeping the two races apart was so normalized that it was ignored schools were learning institutions meant for everyone.

“We were kids,” said Harris. “I went to Keto School, which was an all-black school, and I couldn’t play with the white kids as much anymore because we got split up.”

Cradock High School, in the summer of 1966, was an all-white school. African-American parents who lived in Virginia had not really done much to fight the racism in their communities at that time. However, when letters were sent to their houses to ask if they wanted their child to be selected to integrate the high school, Harris’ parents, wanting the best education for their children, quickly signed the letter.

“There were five boys and two girls,” Harris recalled. “We caught the Douglas bus downtown to catch the Cradock bus. When we walked up to the podium on the stage…the things being slurred…it made me remember where I was. I had several people call me and the others n****** and things, but we learned to deal with it and not be hateful back.”

Keeping that attitude, Harris made sure he was going to make the best of his experience at school, and he made history once again by becoming the first black person on Cradock’s wrestling team, finishing second overall in the local division. He also went on to serve in the U.S Military and graduate with his Associate’s Degree from Tidewater Community College. “At that point it barely mattered about race,” Harris said proudly. “Before I never gave it much thought. I just feel that it was something I was supposed to do. Maybe as I get older, it will begin to dawn on me more.”

You may also like

-

UWG’s Ingram Library Hosts Pop-Up Study Spot to Help Students Prepare for Finals Week

-

UWG Offers Mental Health Support And Academic Services To Maintain Student Success During Finals Week

-

UWG Alumnus Shares His Experience Exploring the Underground Flood Channels of Las Vegas

-

Georgia Students Simulate the Struggles of Dementia

-

UWG PR Students Score a Georgia Power Tour at Atlanta Corporate Office